GeoVanna Gonzalez: HOW TO: Oh, Look at me | By Laura Novoa

Text by Laura Novoa, Curatorial + Public Programs Associate at Bakehouse Art Complex, Miami

HOW TO: Oh, look at me is a film that captures the multi-layered, interdisciplinary performance conceived by GeoVanna Gonzalez as an activation of her sculptural installation of the same name on view at Locust Projects through May 22. Through the performance, which features an original musical score by Batry Powr and involves two dancers, Cheina Ramos and Alondra Balbuena, and poets, Zaina Alsous and Arsimmer McCoy, the installation is transformed from a static form to a space that encourages contemplation, meditation and connection.

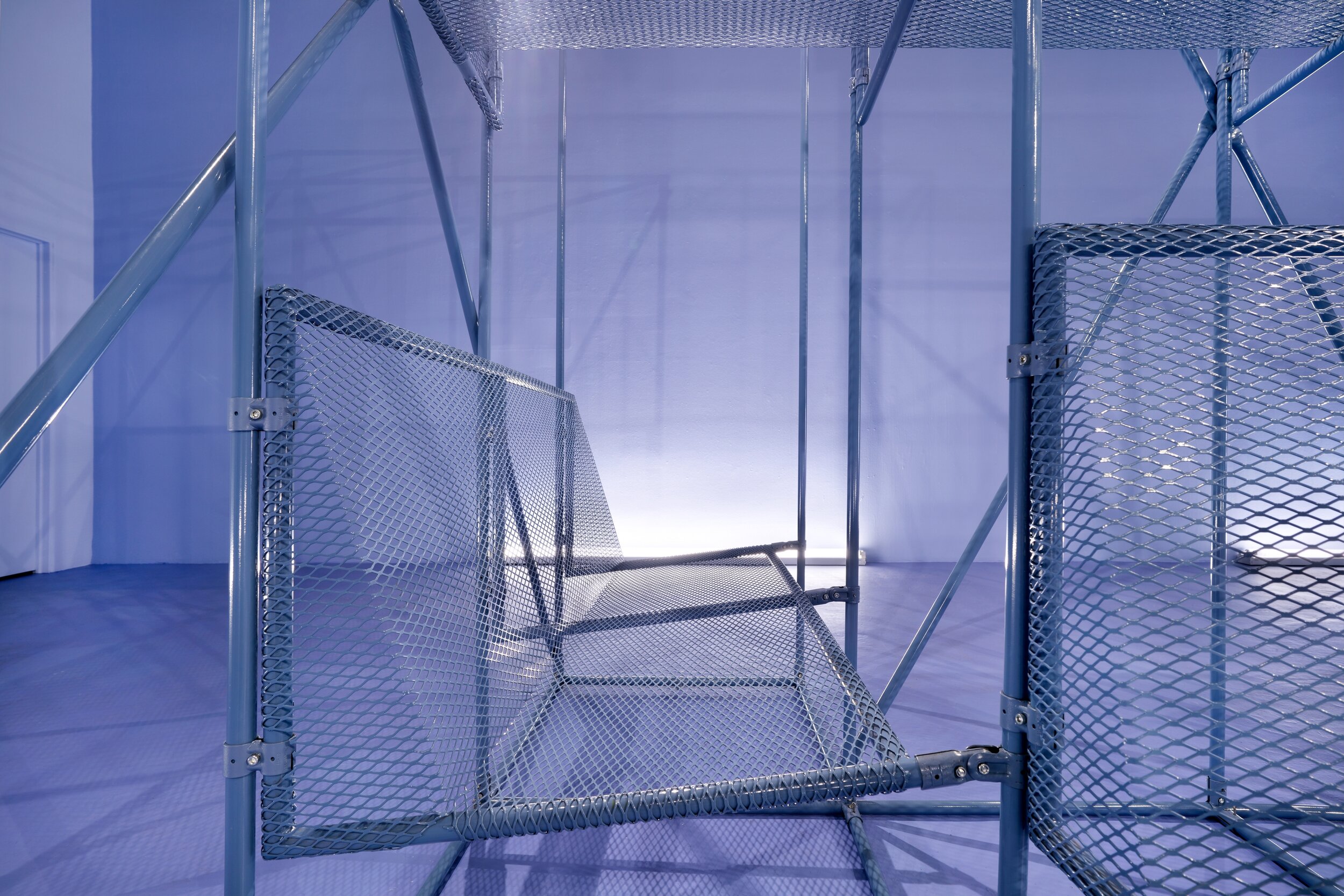

The monochromatic structure consists of multi-level seating components accessible via two central staircases. HOW TO: Oh, look at me is designed to represent the technological grid systems that shape our modern-day personal relationships and social exchanges. Its minimalist, geometric composition is reminiscent of British artist Liam Gillick’s work, particularly Annlee You Proposes (2001), which like Gonzalez’s installation, features an aluminum structure accompanied by video elements and fluorescent lighting.

Within the contextual framework of Nicolas Bourriaud’s relational aesthetics (1), Gillick's architectural structure can be installed in variable configurations depending on the space and location. The changeable and mutable nature of Annlee You Proposes facilitates a multiplicity of scenarios that act as a conduit for social connection and personal encounter. Similarly, HOW TO: Oh, look at me is participatory in nature; yet, Gonzalez envisions her work, not solely as one that, like Gillick’s, is fully realized through human intervention and interaction, but, as one that pushes for collective discourse around liberation. HOW TO: Oh, look at me is about reprogramming the binary, heteronormative, monolithic views around race, gender and sexuality and claiming space for “artists and activists, POC, womxn, queer, trans and gender non-conforming folks, who navigate their art as a form of self-empowerment.”(2)

In the film, through the dancers and poets who interact with and within the structure, Gonzalez explores how we navigate the realities of our virtual existence: “Both online and offline, we experience the world and each other through the screen, justifying our presence through images and videos. Are we really there if we didn’t document it? Are we really seeing someone for who they are or something for what it is if not mediated through a screen?” (3)

The presence of the body and the way it intervenes with the structure alludes to the possibilities of the digital realm, not as cold, detached and isolated, but as a space to challenge, dissent, innovate, and create: “to joyfully immerse [ourselves] in the in-between.” (4) Exploring this in betweenness is a prevalent theme in Gonzalez’s work. In When we open every window, Part II (2020) and PLAY, LAY, AYE | ACT II (2019) she activates modular sculptures through a series of performances that challenge the traditional separation between public and the private spaces. In her essay, The Foreigner’s Home, Toni Morrisson asserts that the power of literature is its demand to “experience ourselves as multidimensional persons.” (5) Gonzalez’s work invites us to apprehend this complexity, to visualize spaces that allow us to immerse ourselves in “the disorienting influence of an excess of realities: heightened, virtual, mega, hyper, cyber, contingent, porous, and nostalgic.” (6)

The film begins with the two dancers facing each other, walking slowly as they glance up to meet each other’s gaze. They gently embrace and clasp hands, momentarily pulling away before approaching the structure and sitting down side by side. They sway and lift their arms, looking at their hands as if affirming that they are there, before separating towards different parts of the structure. The dancers execute controlled, restrained movements in canon, moving in and around the structure independently, separately, following an invisible trajectory. The choreography expresses the removed and alienating feeling of technology, while also incorporating the organic, visceral nature of the human body and face-to-face communication. The music is composed of amorphous sounds synthesized to expand and contract until they become individual notes in their simplest form. Simultaneously, Arsimmer McCoy recites her poem, written in accompaniment of, and response to, the movements and the music around her:

Somebody come find me.

I need hands that make me feel like

I ain't done yet.

I need fingers to trace the parts that are still evolving.

Letting me know some silent evolution is happening.

Throughout the performance, the dancers find moments of encounter: their eyes meet briefly or they reach out longingly before continuing their course. It is in these momentary, albeit intense, interactions of intimacy and proximity that we are reminded of ourselves through the other. In her poem, Scaffolding: After Alice Walker, Zaina Alsous recites: the public is our only problem The public is not a problem melt the middle barrier off each bench so we can finally lay to rest Arms touching shadows touching.

The film, as a receptacle of different languages — spoken, gestural, musical — that come together in their singular agency to create a communal whole, functions as an added layer of meaning, a translation of a translation. Through the performance, Gonzalez examines how forms of communication and miscommunication, both in person and mediated, reflect our self-awareness and condition our perception of those around us. The structure is Gonzalez’s visual interpretation of Martin Jackson’s poem, “No Rothko,'' created through a series of errors that developed from a voice to text algorithm. It is these “errors” — the misunderstandings, the technological glitches, the anomalies of language — that enable the creation and manifestation of alternative narratives and possibilities for living. In Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto, Legacy Russell defines an error as “unpredictable...to become an error is to surrender to becoming unknown, unrecognizable, unnamed.” (7) In HOW TO: Oh, look at me, the error is embraced by the dancers, poets, musician, even Gonzalez herself, who refuse to subscribe to a singular definition of the self. What is liberation if not the possibility of multidimensionality? HOW TO: Oh, look at me is a celebration of ambiguity, an opportunity to cultivate, without limitation, the intersectional realities of who we are and choose to be.

The diversity of mediums simultaneously occurring and occupying creates a living installation where each of the performers is communicating with and in spite of one another. HOW TO: Oh, look at me is a compendium of movements, sounds, voices: a space for otherness. Look at me. Oh, look at me. We have to start now. The last lines of Martin’s poem are an affirmation of existence: a plea to be understood, as much as a stance in defiance.

(1) Bourriard defines relational aesthetics as “a set of artistic practices which take as their theoretical and practical point of departure the whole of human relations and their social context, rather than an independent and private space.” For more information see: Nicolas Bourriaud, Relational Aesthetics (Dijon, France: Les Presses Du Réel, 1998).

(2) GeoVanna Gonzalez, “PLAY, LAY, AYE | ACT II,” last modified June 2019, https://geo-vanna.com/PLAY-LAY-AYE-ACT-II.

(3) GeoVanna Gonzalez, unpublished PDF for film preparation, January 2021.

(4) Legacy Russell, “Introduction,” in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books, 2020), 11.

(5) Toni Morrisson, “Literature and Public Life,” in The Source of Self-Regard: Selected Essays, Speeches, and Meditations (New York, NY: Vintage International, 2019), 100.

(6) Ibid.

(7) Legacy Russell, “Glitch as Error,” in Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (Brooklyn, NY: Verso Books, 2020), 74.

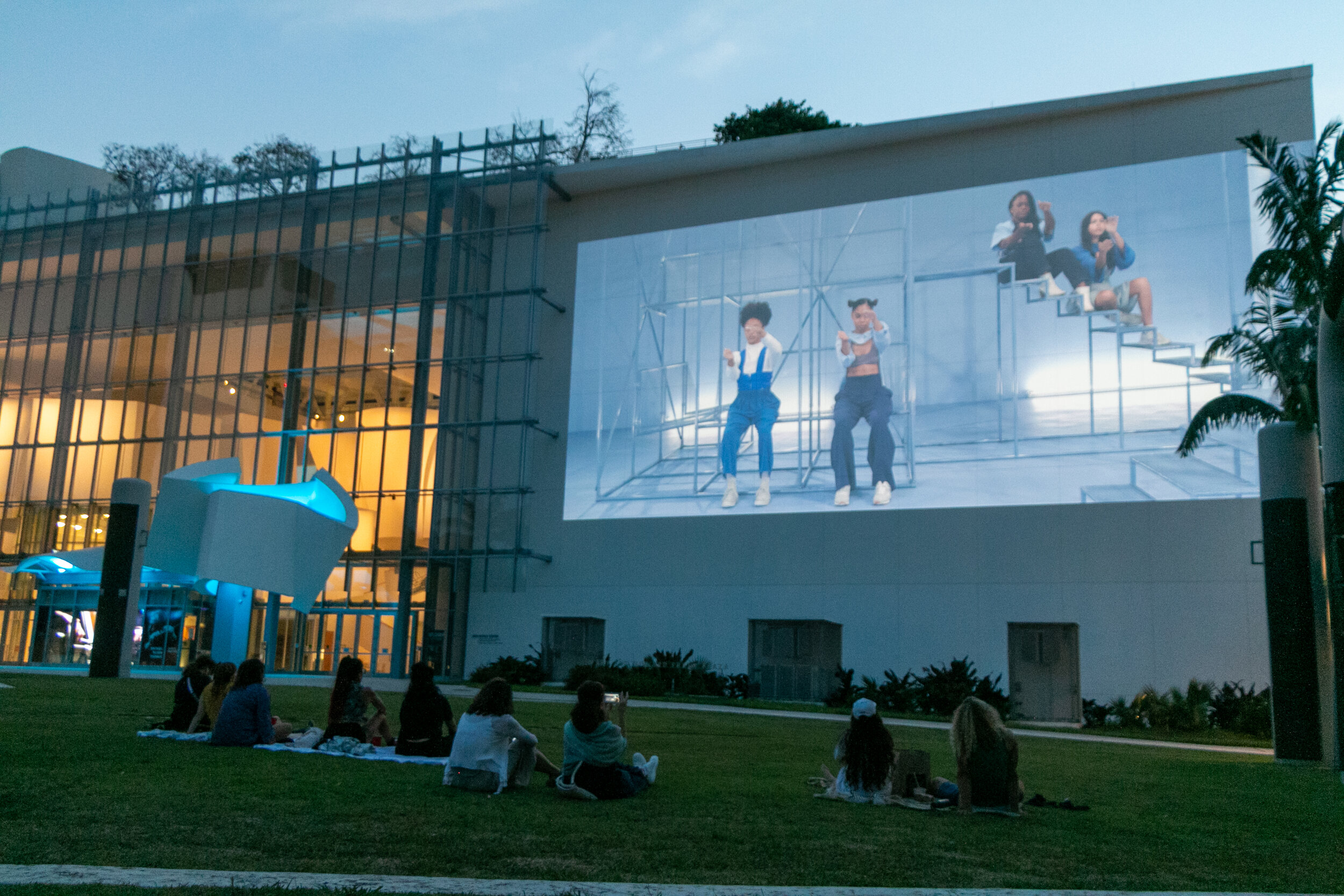

HOW TO: Oh, look at me premiered to the public for free at New World Symphony’s SoundScape Park on April 15 from 7:30-9:30pm in conjunction with the City of Miami Beach’s Culture Crawl and Poetry Month. Presented in conjunction with the artist’s current exhibition on view through May 22, the public screening of the new video at the spacious outdoor venue at SoundScape Park provided a safe, socially-distanced means of exchange and engagement essential to Gonzalez’s work. Highlights from the event below:

GeoVanna Gonzalez: HOW TO: Oh, look at me is commissioned by Locust Projects and made possible, in part, with support from Oolite Arts, Diaspora Vibe Cultural Arts Incubator (DVCAI), and Pulp Arts. The video is commissioned by Locust Projects in partnership with Miami Light Project, Kismet Creative Studio, and Commissioner, and premieres on April 15 in SoundScape Park thanks to additional support from the City of Miami Beach Department of Tourism and Culture, Cultural Affairs Program, Cultural Arts Council and the Miami Beach Mayor and City Commissioners.

Special thanks to: Poet & writer of 'no rothko': Martin Jackson. The cast: Cheina Ramos and Alondra Balbuena, Arsimmer McCoy, Zaina Alsous, Batry Powr. And to the crew: Monica Sorelle, Jessica Bennett, Juan Luis Matos, Jon Kane, Javier Labrador, Iris Beatrix, Eddy Moon, Karo Ruiz, David Ortiz.

ABOUT GEOVANNA GONZALEZ

GeoVanna Gonzalez is a Miami/Berlin-based artist and curator. Her work desires to connect private and public space through interventionist, participatory art with an emphasis on collaboration and collectivity. She builds installations that are designed for non-directive play in order to express the potential of our embodied cognition. She references architecture and design by reflecting on how the voids in the spaces we inhabit affect our everyday. Through her work she addresses the shifting notions of gender and identity, intimacy and proximity, and forms of communication and miscommunication in today’s technological and consumer culture. Her most recent work performs these possibilities by collaborating with movement and sound based artists. These improvisations are political acts, analyzing and critiquing what it means to share public space as womxn, queer folks and people of color. She is founder and curator of Supplement Projects, an alternative art space & community meeting point based in Miami; co-founder of performative reading club Read What You Want!; and member of queer/feminist arts collective COVEN Berlin.

Photo: World Red Eye

Locust Projects 2020-2021 exhibitions and programming are made possible with support from: The John S. and James L. Knight Foundation; The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts; The Miami-Dade County Department of Cultural Affairs and the Cultural Affairs Council, the Miami-Dade County Mayor and Board of County Commissioners, The Children's Trust; Berkowitz Contemporary Foundation; The National Endowment for the Arts Art Works Grant; Hillsdale Fund; the Albert and Jane Nahmad Family Foundation; VIA Art Fund | Wagner Incubator Grant; Funding Arts Network; The Jorge M. Pérez Family Foundation at The Miami Foundation; Susan and Richard Arregui; Kirk Foundation; Miami Salon Group; Scott Hodes; Jones Day; Community Recovery Fund at The Miami Foundation and the Wege Foundation; and the donors to the Still Making Art Happen Campaign and Locust Projects Exhibitionist members.